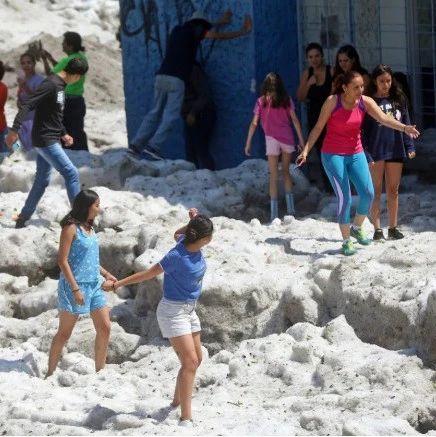

Six suburbs in the Mexican city of Guadalajara were carpeted in a thick layer of ice after a heavy hailstorm.

© Image | Google

The ice was up to 1.5m (5ft) thick in places, half-burying vehicles.

Civil protection machinery was deployed to clear streets in the city of five million located north of the capital, Mexico City.

© Image | Google

Local officials also reported flooding and fallen trees, but no-one is thought to have been hurt. The storm hit very quickly, between about 01:50 (06:50 GMT) and 02:10 local time, when the air temperature dropped suddenly from 22C to 14C.

The city had been basking in temperatures of more than 30C. It has been hit by hail storms before, but seldom this heavy.

© Image | Google

What causes a hailstorm?

Hailstorms form when warm, moist air from the surface rises upwards forming showers and storms. Temperatures higher up, even in summer, can get well below 0C and so ice crystals form along with something called “supercooled water” which then grows into pellets of ice.

© Image | Google

In severe thunderstorms, air can rise rapidly and is able to hold up these hailstones and allow them to expand in size. Eventually, they get too heavy and fall to the ground.

In warmer parts of the year, such as in Guadalajara which has maximum temperatures of around 31-32C in June, more moisture is available, contributing to the formation of hailstorms.

© Image | Google

Temperatures this month have been higher than normal with Torreon, to the north of Guadalajara, reaching highs of 37C.

The authorities say 200 homes have been damaged and dozens of vehicles swept away in the city and surrounding districts.

State governor Enrique Alfaro described it as incredible, according to AFP news agency.

© Image | Google

“Then we ask ourselves if climate change is real. These are never-before-seen natural phenomena,” he said.

© Image | Google

According to BBC Weather, the hail probably melted on contact due to the high temperatures forming a layer of water upon which more hail could land and float.

This combination of water and hail likely moved downslope, with obstacles such as buildings blocking the flow and allowing more ice to accumulate on top.

The actual hailstones were relatively small, less than 1cm in diameter, and nothing like the golf-ball sized hail seen at times in severe storms in the US.